Last night I dreamt about Jacobo Glantz, an aging poet from Ukraine who had emigrated to Mexico in the 1930s where he founded the Jewish Press and became known as translator of contemporary Russian poetry as well as one of the most significant Yiddish poets then writing.

What provoked this dream? Our dreams have changed and acquired new, sometimes surprising, contours during this Coronavirus pandemic of 2020. Perhaps it is our current isolation that sends us back in time. I frequently find myself revisiting moments from much earlier in my 84 years. In last night's wanderings I smiled as I watched Jacobo in his familiar corner at the back of the restaurant he owned in Mexico City's Zona Rosa. He was writing on a typewriter whose carriage he threw in the opposite direction from those with which I was familiar. The restaurant was a deli-type eatery where poor poets knew we could always have a meal on the house. Jacobo was generous in his encouragement and support of younger artists. He also had an art gallery next door.

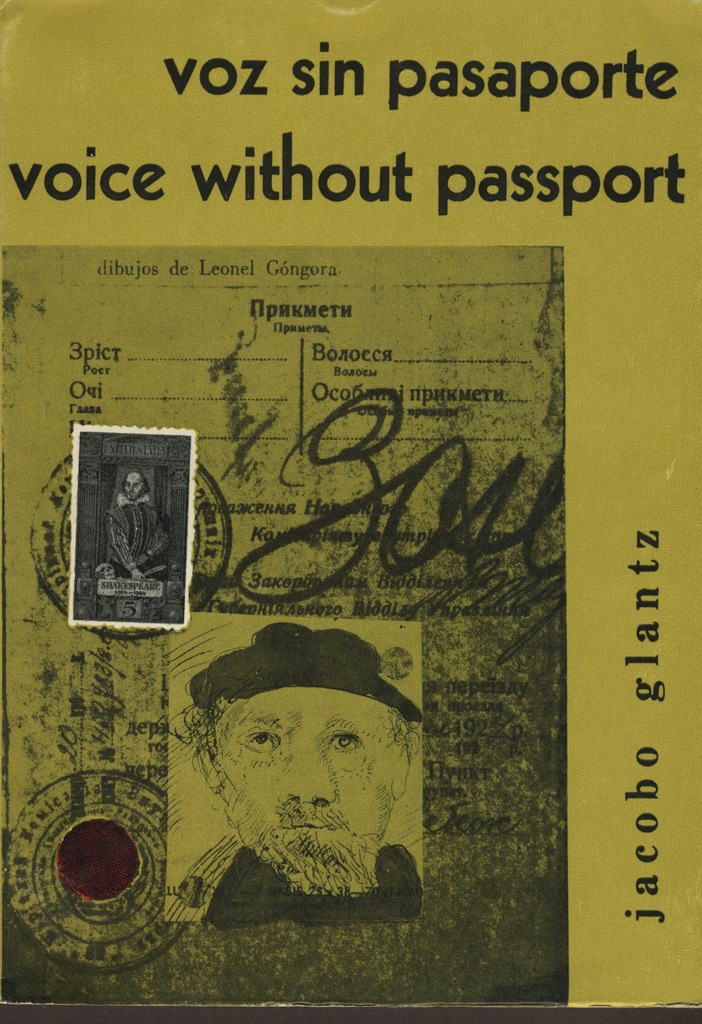

Dreaming about Jacobo reminded me that we published a bilingual collection of his poetry in 1965: Voz sin pasaporte / Voice Without Passport. The English translation is by my mother, Elinor Randall, who often translated for us throughout the 1960s. The slim volume is illustrated with drawings made especially for it by Leonel Góngora, a Colombian artist who was also one of Mexico's brilliant transplants. He used pages from Jacobo's passport in his evocative collages. Upon awaking this morning, I went to my bookshelf and found a copy of Voz sin pasaporte. It is number VI in what we called our Colección Acuario, one of several imprints El Corno produced in addition to the 31 quarterly issues of the magazine.

El Corno Emplumado / The Plumed Horn published its first issue in January 1962. We produced one every three months until the middle of 1969 when the repression following Mexico's Student Movement of the year before forced me to flee the country. That repression meant the death of what had been an exciting literary/artistic project, publishing more than 700 writers from 35 countries, many of them bilingually. During our first two years, the fourth issue of each year was a bilingual book by a single poet, one year a book by a poet writing in Spanish, the next year by one writing in English. By 1964, though, we were hesitant to devote a whole issue to a single person. We were receiving more good work than we could accept, and we needed the journal's pages for the dozens of writers who inspired us—from Mexico to Argentina, Finland to India, Nicaragua to the US and many other parts of the world.

This led to our conceiving of a series of small books by individual poets and writers. Also visual artists. We began accepting manuscripts, pairing them with translators and illustrators, and initiated a series we called Colección Acuario. Number I in the series was Majakuagymoukeia, the creation story according to the Cora Indians of Mexico's western coast of Nayarit. This sacred book had been recorded by a woman who called herself Ana Mairena. Married to the governor of the state of Nayarit, she felt she should use a pseudonym in her oral history work. I never learned her real name. Again, my mother produced the English translation, and 1,000 copies of the book were printed.

Number II in our Colección Acuario is Trophies of the Sun /Trofeos del Sol by US poet Roger Taus. Lucy Sabugal did the Spanish translation, and the very slim volume is illustrated by a variety of artists: Bartolí, Enrique Bessonart, Juan Calzadilla, Jaime Carrero, Jose Delarra, Alice Garver, Alberto Gironella, Daniel González, Irving Kriesberg, Cirilo Salgado, and Michelle Stuart. I wonder now if these visual artists had sent their drawings to El Corno and we decided to use them in this book instead of in the journal. Once again, we printed 1,000 copies.

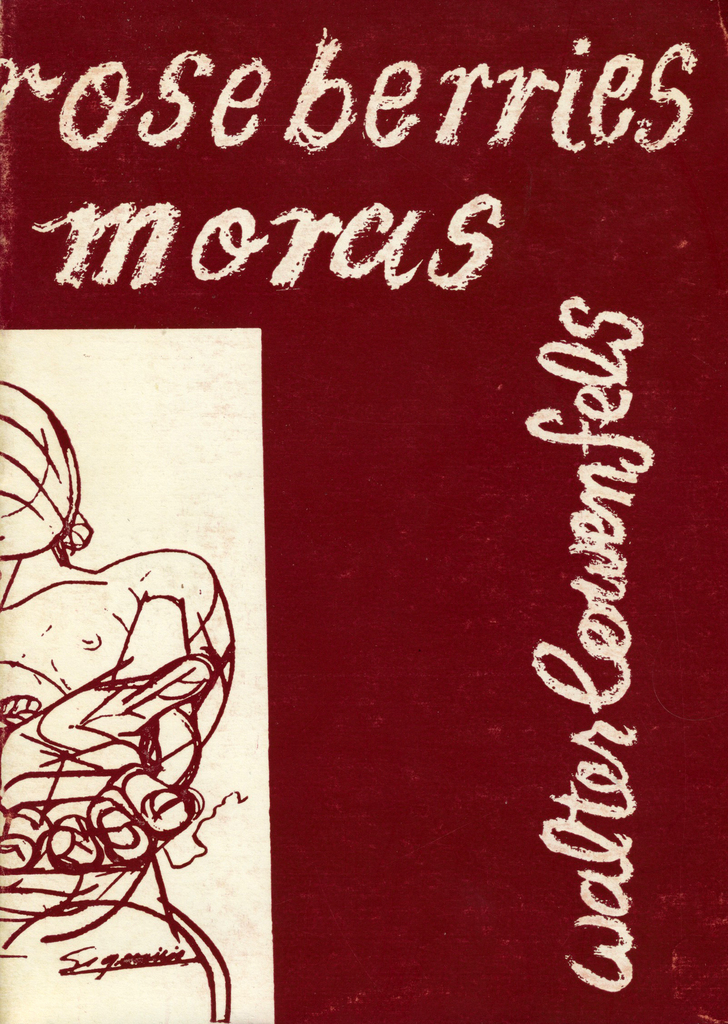

Colección Acuario's volume number III was Tenebra by Venezuelan poet Ludovico Silva. Sergio Mondragón and I did the English translation, and the book is illustrated by Julius Tobias, a New York artist active at the time. Number IV in the collection was Land of Roseberries / Tierra de Moras by the great US Communist poet Walter Lowenfels. Walter and his wife Lilian suffered persecution during the McCarthy witch hunt; he was imprisoned for a year and she lost her job as a teacher, suffered a stroke and remained partially paralyzed for the rest of her life.

The Lowenfels visited us in Mexico in 1964. Walter introduced us to a number of fine poets whose work was not being published because they were leftist, black, Hispanic or their work reflected social themes. For this book-length poem, the great Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros gave us a series of drawings he made especially for the occasion. Sergio and I did the Spanish translation. The book appeared in 1965 in an edition of 1,000, but this time—perhaps because we knew we were publishing a masterpiece in word and image—we produced an additional 50 copies that were leatherbound, signed by the author and artist, and sold to benefit our publishing project.

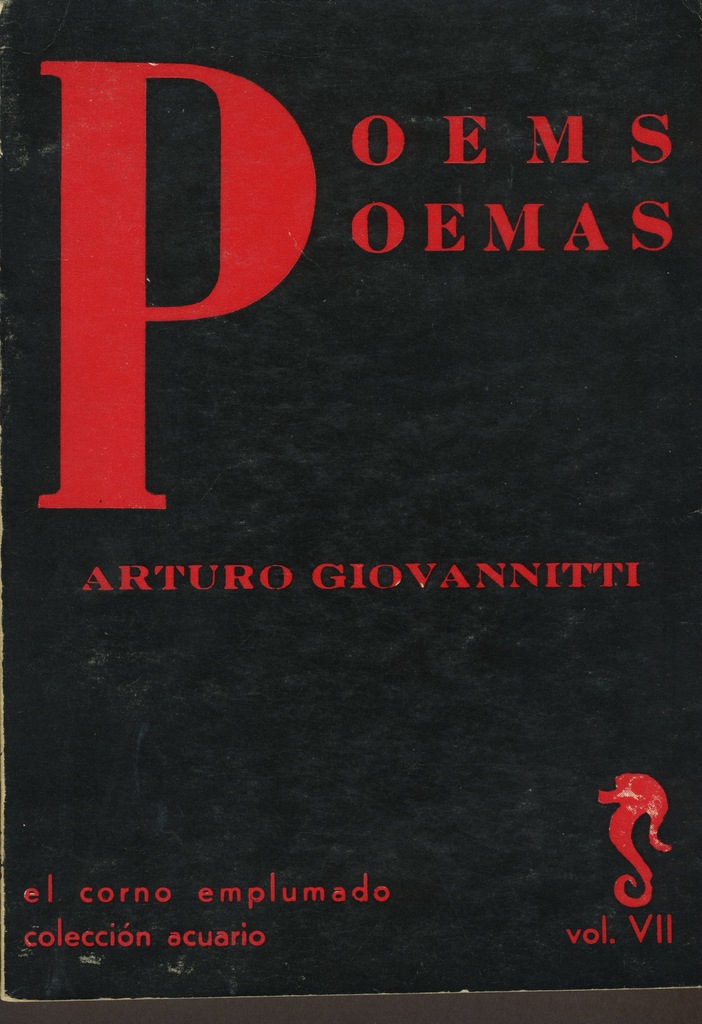

Sergio's Yo soy el otro / I Am the Other was number VI in our Colección Acuario. I did the English translation of the poems, and Canadian artist Arnold Belkin who lived in Mexico provided original drawings. Jacobo Glantz's book, as mentioned, was number VI. Number VII was another find, brought to our attention by Lowenfels. It is by Arturo Giovannitti and titled simply Poems /Poemas. The Spanish translations are by the great Catalán poet Agustí Bartra, who took refuge in Mexico following the Spanish Civil War. Bartra was a frequent contributor to El Corno; our fourth issue was his bilingual book Marsias & Adila. A note included in the book reads: "Agustí Bartra translated nine of the eleven poems here published. The last two were left only in the original English through agreement by translators and publishers that Spanish versions could not hope to do justice to their complicated verse pattern (interior, as well as end of line, rhyme)."

Giovannitti himself was born in Campobasso, Italy, and emigrated to Canada and then the United States where he was instrumental in forming labor unions. The poet was one of the leaders of the Lawrence, Massachusetts textile workers strike of 1912. Because that strike involved several deaths, he was imprisoned for ten months but eventually released. Helen Keller was a devotee of Giovannitti's work. He died in 1959.

Number IIX in the collection is Miguel Donoso Pareja's Primera canción del exiliado / The Exile's First Song. We clearly weren't all that familiar with Roman numerals, or we would have numbered this book VIII instead of IIX. Donoso Pareja was a well-known poet and teacher of poetry from Ecuador, who—like so many leftist intellectuals of those years—sought political refuge in Mexico. He was in hiding in his country but emerged one night to take two of his daughters to the movies. That's when government forces captured and imprisoned him. He was later released on the condition that he leave Ecuador and he sought refuge in Mexico. Mexico's policy of taking in exiles from Europe during World War II and Latin America during the Dirty Wars of the 1970s and '80s greatly enriched its artistic and scientific communities. The Exile's First Song was translated by my mother and enhanced with original drawings by Colombian painter Pedro Alcántara.

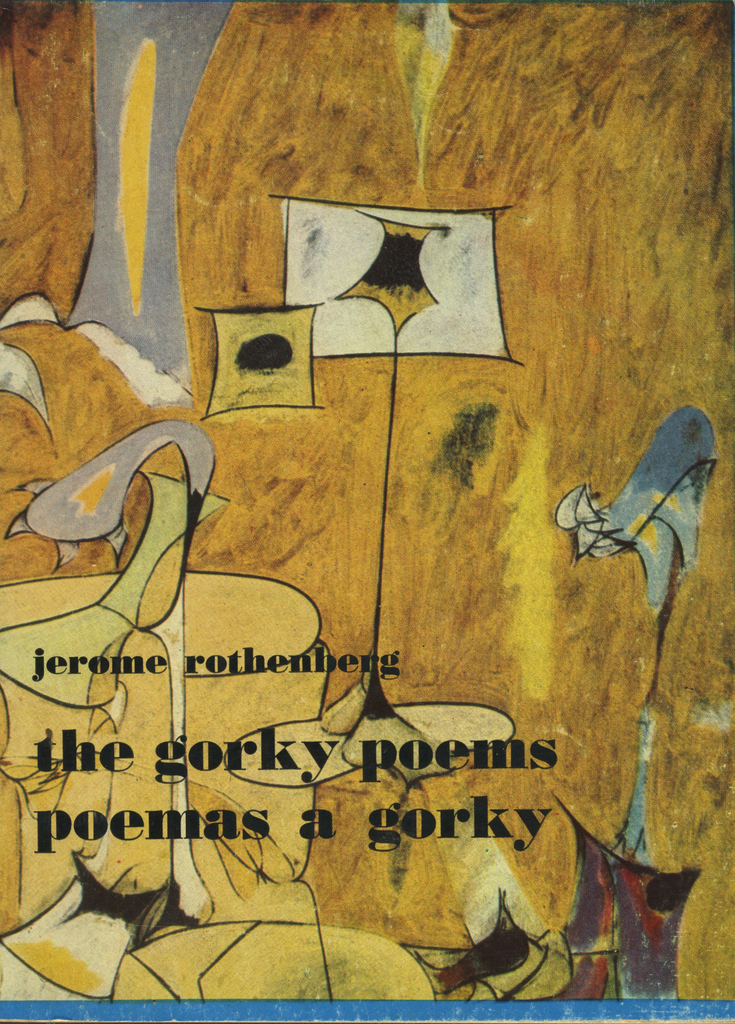

The next book in the series, number IX, was another treasure. It is US poet Jerome Rothenberg's The Gorky Poems / Poemas a Gorky. Sergio did the Spanish translation and we confidently (or shamelessly, depending on your point of view) used a detail of Arshile Gorky's "Betrothal" on the cover. We acknowledged that the painting belonged to the Whitney Museum of American Art but didn't ask the museum's permission; we knew we would not have received it. Rothenberg's long poem was written out of his involvement with New York's abstract expressionists of those years; I was similarly inspired by them and had asked to publish the manuscript. For that reason, Rothenberg dedicated the book to me and Sergio.

I do not own a copy of Colección Acuario Number X. After some research online, I discovered that it is In the Country of a Deer's Eye / En el país del ojo de venado by US poet and editor C. W. Truesdale. The art and front cover are by Ecuadorean visual artist Judith Gutiérrez, who was closely connected with El Corno. This may or may not be the only title missing in my collection. And I have not been able to find out who did the Spanish translation. One of the beautiful things about recording this history is that others can add to it, providing additional memories and filling in the blanks. If I am missing other titles, I hope those who know about them will come forward with the information.

Number XI, the last book in the Colección Acuario is a volume of short stories Prontuario / Compendium by Venezuelan writer and economist José Moreno. Throughout Latin America it was common in those years for writers to also be economists of have other professions. Moreno's fellow compatriot Hugo Baptista did the drawings for the book and the English translation was, again, by my mother.

In a period of three years, between 1964 and 1967, El Corno's Colección Acuario published eleven titles under that imprint. But those weren't all the books we produced. Three additional books were released during the same period in a series we called La Llave. I can no longer remember why we differentiated between Acuario and La Llave. The only clue offered by the books themselves is that Acuario's titles were all bilingual while La Llave's were in English only. La Llave number I was The Trees or The Trees of Vietnam (the name varies from cover to title page) by Finnish poet Matti Rossi in English translation by another fine Finnish poet, Anselm Hollo. The Trees was a series of poems protesting the US American war in Vietnam. The book's cover was designed by Rumanian/Mexican visual artist Sylvia de Swaan, who had contributed drawings to the magazine.

Volume II was Robert Kelly's book-length poem Weeks. This title enjoyed the dubious distinction of having the entire print run destroyed, something the author demanded because it was riddled with typos. This was one of those experiences that taught us the hard way how important careful proofing is. Erik Kiviat's Museum of Memmon was La Llave number III. Details of photographs by Madeline Landau highlight the text. All titles in the La Llave series were published between 1964 and 1966 and all also consisted of 1,000 copies.

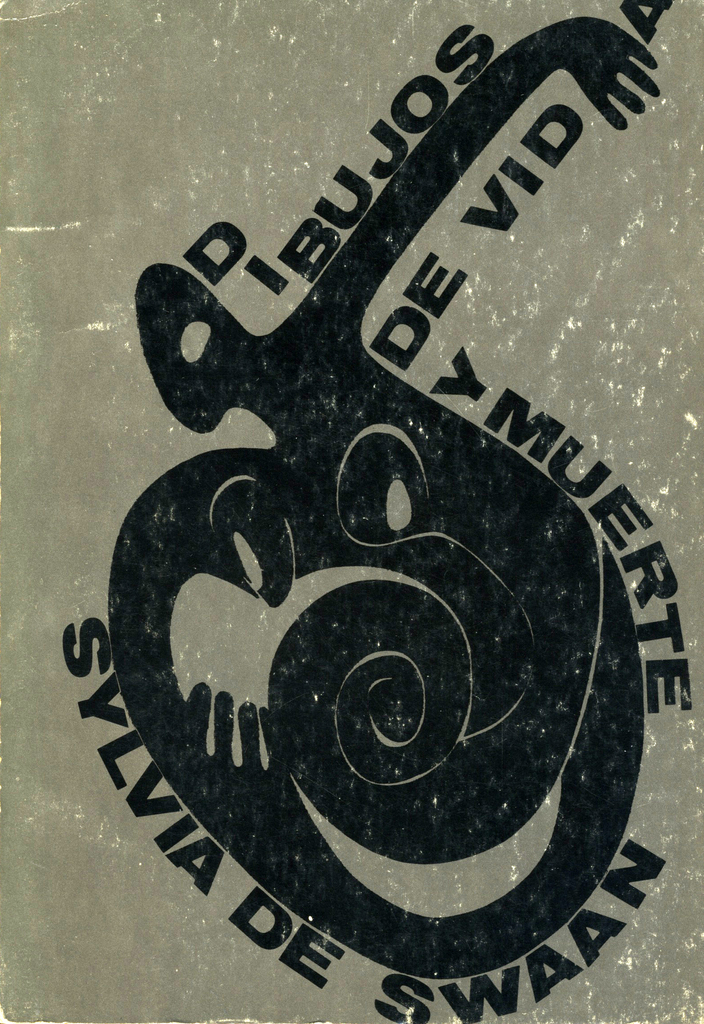

Our Colección La Ola produced a single title, Dibujos de vida y muerte / Drawings of Life and Death by Silvia de Swaan. This book of line drawings opens in one language from front to back and in the other from back to front. Scattered among the evocative images are brief texts by Philip Larkin, Agueda Ruiz, Sergio Mondragón, Horacio González Martínez and myself. If I remember correctly, Sylvia chose the texts she wanted to illustrate her drawings. El Corno always emphasized respect for genres in every direction; visual art might accompany the written word, literary texts might accompany drawings, or—more often than not—each genre was treated independently.

We would produce six more books before we were forced to cease publishing. These did not bear a particular imprint or belong to a named collection. They stood alone, simply produced by El Corno Emplumado Press. I'm not sure why. They were all published between 1964 and 1967 and are, in order of appearance: A Reconciling of Rivers by New York poet Marguerite Harris (with a single drawing by Bartolí); October (poems by me with photographs by Japanese sculptor Shankichi Tajiri); The Small Waves (a novel by US writer Alvin Greenberg with interior drawings and the back cover by Don McIntosh); This Do (& The Talents) by US poet Theodore Enslin; Set in a Landscape (poems by David Ossman and lithographs by Mowry Baden); and finally Water I Slip into at Night (my poems with drawings by Felipe Ehrenberg). This last title had an edition of 1,500 copies, the first 30 of which were leatherbound and the drawings were hand-colored by the artist. Ehrenberg was a Mexican artist who was close to El Corno from its inception. He provided three of the magazine's covers and interior art for several issues.

There is an interesting story connected with my book October. The printer was well into producing the large 16-page signatures when he noticed that the photographs depicted female nudes interacting with Tajiri's phallic sculptures. He was outraged and refused to finish the job. We had to haul those unbound signatures to another print shop whose owner wasn't so puritanical.

This brief overview of the books published by El Corno Emplumado in addition to the regular issues of the magazine leaves some memory gaps due to age and to the fact that moving from country to country, sometimes under very difficult conditions, meant that I do not have a complete collection. As I've already said, there must have been a number X in our Colección Acuario, and there may well have been another title or two (or three) published after those I have in my library. The other collections—La Llave, La Ola, and those lacking an imprint—may also have had titles I no longer possess. All these books are out of print and available only in rare and extremely expensive editions. With or without the missing volumes, and like the magazine that launched them, they include important writing and visual art from the mid-twentieth century.

--Margaret Randall

Albuquerque, October 2020.

Editors Note: This essay accompanies a new collection of book cover images for the 21 books published in Ediciones el corno emplumado. To see the full collection, click here