(Sergio Mondragón gave this talk in Mexico City on January 16, 2015, at the University of Mexico’s Tlatelolco Cultural Center as part of a panel on El Corno Emplumado. Translation: Margaret Randall.)

El Corno Emplumado’s editorial adventure began for me almost casually toward the end of 1961. I was finishing up my journalism studies and doing some reporting for the Mexican magazine Revista de América. It was October, and I’d just interviewed the painter David Alfaro Siqueiros in prison; he was a political prisoner at the time. Among much else, I’d asked him about his relationship with the US painter Jackson Pollack, and the supposed influence the Mexican muralists had on that school of which Pollack was a pioneer, the school that in the United States would later be known as Action Painting.

I was immersed in writing and researching that interview, when my classmate at the school of journalism, the poet Homero Aridjis—who had just published his first book—invited me to meet the Beat poet from San Francisco, California, Philip Lamantia. Philip had arrived in Mexico City shortly before.

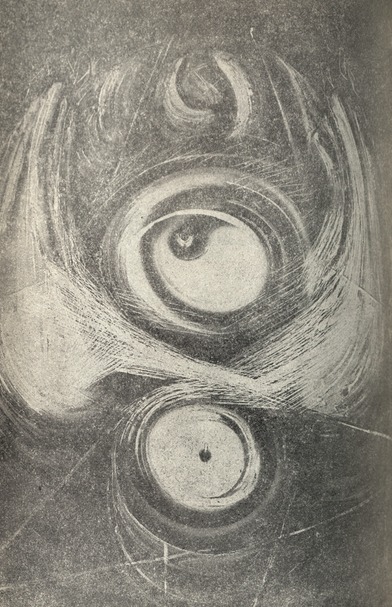

That meeting was a revelation. At Lamantia’s apartment the group of poets who were gathered immediately began to read in their respective languages. Soon after, Lamantia called to say he wanted to introduce us to Margaret Randall, recently arrived from New York. That very night we were once again reading our poems to one another. The walls of Margaret’s apartment were covered with paintings she’d brought with her, abstract expressionist works. This was a painting style I was seeing for the first time (outside of books), and its aesthetic would have a certain influence on the magazine. All this helped me put the finishing touches on my feature about Siqueiros (and that artist would later illustrate the book we devoted to the North American poet Walter Lowenfels).

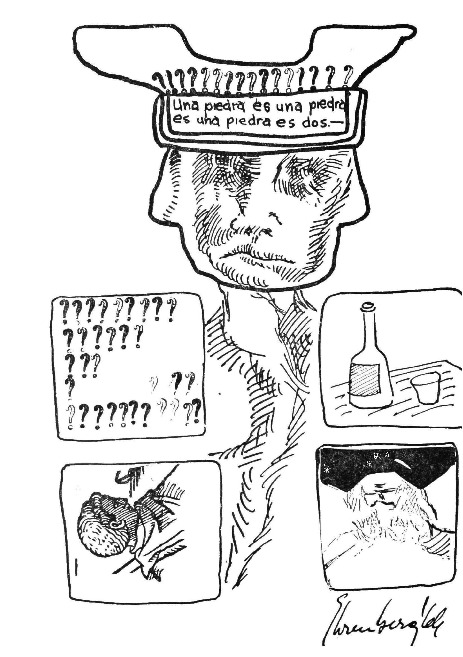

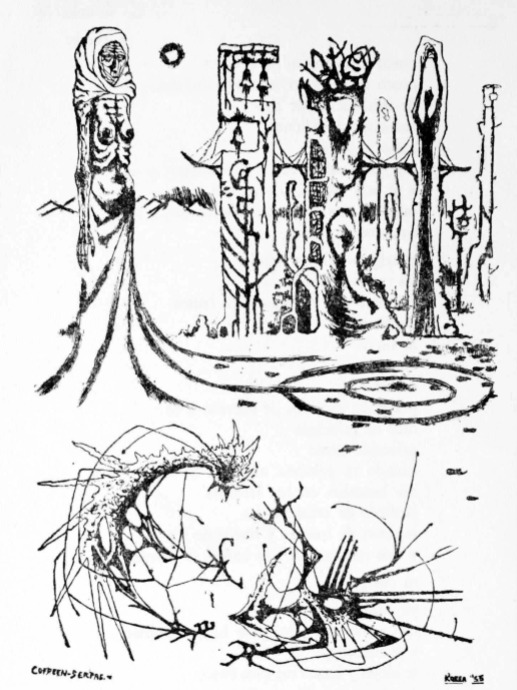

From then on, it was a whirlwind. We began to make translations and, once the word was out, other poets came around: the Nicaraguans Ernesto Cardenal and Ernesto Mejía Sánchez, both of whom lived in the city; the Mexican Juan Martínez, painters Felipe Ehrenberg and Carlos Coffeen Serpas, and US poets Ray Bremser and Harvey Wolin. It was at one of those gatherings that the group “discovered” the lack, and “saw” in the magic that had brought us together the opportunity or need for, a magazine that would showcase “both worlds”: that of Hispano-American poetry and that of poetry from north of the border. In other words, the poetry being written at the time on the length and breadth of the Continent.

We soon baptized the magazine with the name El Corno Emplumado / The Plumed Horn (alluding to the jazz horn of the United States and Quetzalcoatl, the plumed serpent who was the iconic god of Mesoamerica’s pre-Hispanic cultures). Although none of the three of us had previous editing experience, Margaret Randall, Harvey Wolin (another Beat poet who was visiting) and I took charge. The two of them were responsible for the publication’s English side, and I for the Spanish. The money we needed to assure that the first issue would appear in January 1962 we were able to collect during those initial poetry readings.

El Corno was, on the one hand, the search for and encounter with one expression of Mexico’s and Latin America’s modern cultural production: the new Mexican poets no longer wrote the way poets had been writing up to that time, professing a total devotion to formal perfection, the color gray, the discreet tone, a lineal discourse, idiomatic purity, anecdotal transparency, etc. We wanted to break with that world and all that it represented. It had all begun a bit earlier, with the poetry of Marco Antonio Montes de Oca and the prose of Juan Rulfo and Carlos Fuentes (not unlike what was happening in the rest of our countries with respect to their own traditions). On the other hand, in El Corno’s pages the North American poets were following a similar path. They no longer thought or wrote like T.S. Eliot or Ezra Pound, and with a Howl they renounced both a past and a present that felt asphyxiating: the smiling US world that had dropped the Bomb on densely populated Japanese cities and emerged from the Korean war with its conscience in tact and face clean shaven, even as it got more deeply involved in its war in Vietnam, and that shattered anything unwilling to give itself wordlessly to the project of the “American Dream.” The Beats had a dual proposition: a truly liberated language, and a human being who was also liberated but, furthermore, sacred, Beatific, with the right to be considered and treated with respect, and with the potential for building and inhabiting a Nirvana-like world. It was an idea they had borrowed from Asia, an intense, calm and positive world, not to be globalized but to become profoundly personal although readily shared. In both cases, the poetry of El Corno, of those “two worlds,” the North American and the Latin American, gave birth to a language of rebellion, and at the same time it was a legacy bequeathed us by the great masters of the past and of the Vanguard.

The cosmopolitan vocation that, more than merely El Corno’s project was the sentiment that nurtured the era, bore immediate fruits. We distributed the magazine in Mexico, New York and San Francisco. Animated by Margaret Randall’s dynamism—she had exceptional organizational skill and a great capacity for work—and thanks to a list of places where the Fondo de Cultura Económica publishing house sold its books throughout the continent, a list given to us by its director Don Arnaldo Orfila, who looked sympathetically upon our magazine, in a few short weeks El Corno was in bookstores in Buenos Aires, Sao Paulo, Bogotá, Lima, Santiago, Caracas, Quito, La Habana, Managua, Montevideo… And the response was immediate. Soon our post office box was filled with greetings, biographies and submissions. From the Beats we moved on to other schools of North American poetry: Creeley, Olson, Black Mountain. Among the first to get in touch with us were Miguel Grinberg, Haroldo de Campos, Cecilia Vicuña, Raquel Jodorowsky, Pablo Antonio Cuadra, Gonzalo Arango, Alejandra Pizarnik, Edmundo Aray and groups such as the Tzántzicos, Nadaístas, Concrete Poetry, Eco contemporáneo, Techo de la Ballena, City Lights Bookshop… They were attracted to El Corno because of its innovative poetry, experimental typography, ideas and words that sounded real, drawings whose lines were thin incisions on the skin of an era.

And we realized, in both directions, that everywhere the same thing was happening: we were saying goodbye to one era and initiating another. We were experiencing a new human vibration. The Cuban revolution appeared on the horizon like a hopeful dawn (at a time of ferocious military dictatorships throughout Latin America). The whole world was giving birth. It was the energy of the now mythic, horrendous and golden Sixties, dividing the century and our literatures in two—although we had already been served a Vanguard aperitif on the dazzling dinnerware of modern art. In El Corno we called all this that passed before our eyes “spiritual revolution,” and we spoke about “a new man” who inhabited “a new age.” Eco contemporáneo called for a “new solidarity.”

The Mexican poetry anthology produced in 1966 by Octavio Paz, Homero Aridjis, Alí Chamacero and José Emilio Pacheco, and that was titled Poesía en Movimiento (Poetry in Movement), in more than fifty percent of its contents used the work of the new poets, with poems taken from El Corno Emplumado as well as from editorial projects similar to ours, such as Pájaro Cascabel, Cuadernos del viento, Diálogos, El rehilete, La cultura en México, Revista mexicana de literatura… In the prologue to that anthology the editors emphasized the concept they called a “tradition of rupture.”

The power of these events and the originality of the poems and letters we published, the visual art and great web of communication we were able to establish at a time when the Internet had not yet been invented—something Raquel Jodorowsky called “circulación sanguinea de poesía” (the poetry running in our veins)—went far beyond any project El Corno alone could have envisioned. In any case, we shared the great privilege of being a part of it all.

That Pan Americanism, more than a deliberate project, was a fact of the spirit, and as always the politicians appropriated its language. Those were also the years in which The Organization of American States and its cultural branch The Pan American Union emerged. These were instruments intended to submerge Latin America even more completely in underdevelopment (we can see the results today). Ernesto Cardenal was quick to understand those realities, and wrote a letter of messianic tones which we published in January 1963: “The true Pan American Union is that of the poets, not the other… we must struggle until we reach every corner of Latin America, aided now by the Yankee poets… that is another of El Corno’s missions...”

The so-called counterculture was and is, in fact, culture itself: Aureliano Buendía, Pedro Páramo and Artemio Cruz were all countercultural, although they breathed tradition: and so were the lines of Ginsberg’s “Kaddish” and the combination of regular and irregular accents in Octavio Paz’s “Piedra de sol” (Sun Stone). The great youthful rebellions that gave way to today’s world were simply an expression of the crisis.

Our poetic generation lived those years trying to keep up with what was happening and incorporate it into our consciousness. We tried to rise to the demands of our circumstances, learn to be critical, and not take ourselves too seriously. The great modern artists had already sensed and announced it all: cubism breaking down the walls of what was supposedly real (and even before, impressionism blurring the lines). “Something is readying itself,” André Breton had warned. (Or was it Benjamín Peret?) The Sixties with its youthful rebellions and its magazines and its poets, were only the blink of an eye in that barbarous and lovable century; and they contained as much infamy as humanity, something that some of us are trying to begin to assimilate as part of our personal histories. It’s worth repeating here what Gabriel García Márquez said in his book, Vivir para contarlo (Live to Tell): “Life isn’t what one has lived, but what one remembers, and how one remembers it in order to pass it on.”

And so seven years of joyous, painful, arduous activity went by. Until the night of Tlatelolco, October 2, 1968 arrived, that criminal repression, to date unpunished, that Gustavo Díaz Ordaz’ government launched against the Student Movement—a movement that the magazine supported and of which it was a part, just as were the vast majority of Mexico’s artists, writers and intellectuals, and that not only unleashed the fury of death, exile, persecution, suffering, prison, and terror upon so many people—a wound in Mexico’s heart that has bled for decades and may never close, putting an end to the golden dream of the Sixties and to… El Corno Emplumado. Because that was the beginning of the end for the magazine.

The economic support from government institutions ended abruptly, and the “forces of order” hunted down the Movement’s protagonists and many of its sympathizers, those who had escaped with our lives. It dispersed people, forced them to flee, submerged them in silence and into a long and humiliating assimilation of the tragedy. One voice, as we know, raised itself the day after the massacre and in the midst of the confusion that followed. It’s important to remember it. Days after the massacre and from his diplomatic post in India, Octavio Paz renounced his position as Mexico’s ambassador to that country in protest against that which had been perpetrated.

The depth of the historic insult inflicted upon our youth was of such a magnitude that today, almost 50 years later, expositions and events such as these continue to question, interview and write about the Student Movement of 1968, as opposed to the oblivion and indifferent demands in which some still wish to embalm that horrendous history, and resulting from the growing interest that the events of Mexico 1968 continue to awaken. And we can listen to people, weathered by age, with broken voices and holding back their tears, speak of the details of their participation and of the quota of suffering they have had to endure.

![Land of Roseberries / Tierra de moras [Cover] Land of Roseberries / Tierra de moras [Cover]](https://opendoor.northwestern.edu/archive/files/fullsize/5a7c9c2b764df927ab7a0ec891a88af5.jpg)

![Pájaro Cascabel 8 [Cover] Pájaro Cascabel 8 [Cover]](https://opendoor.northwestern.edu/archive/files/fullsize/c49e136988d131d9cfed3721c5bb03da.jpg)

![Diálogos [Cover] Diálogos [Cover]](https://opendoor.northwestern.edu/archive/files/fullsize/dd3f6e14f809a525c1e44d4e962e25b0.jpg)