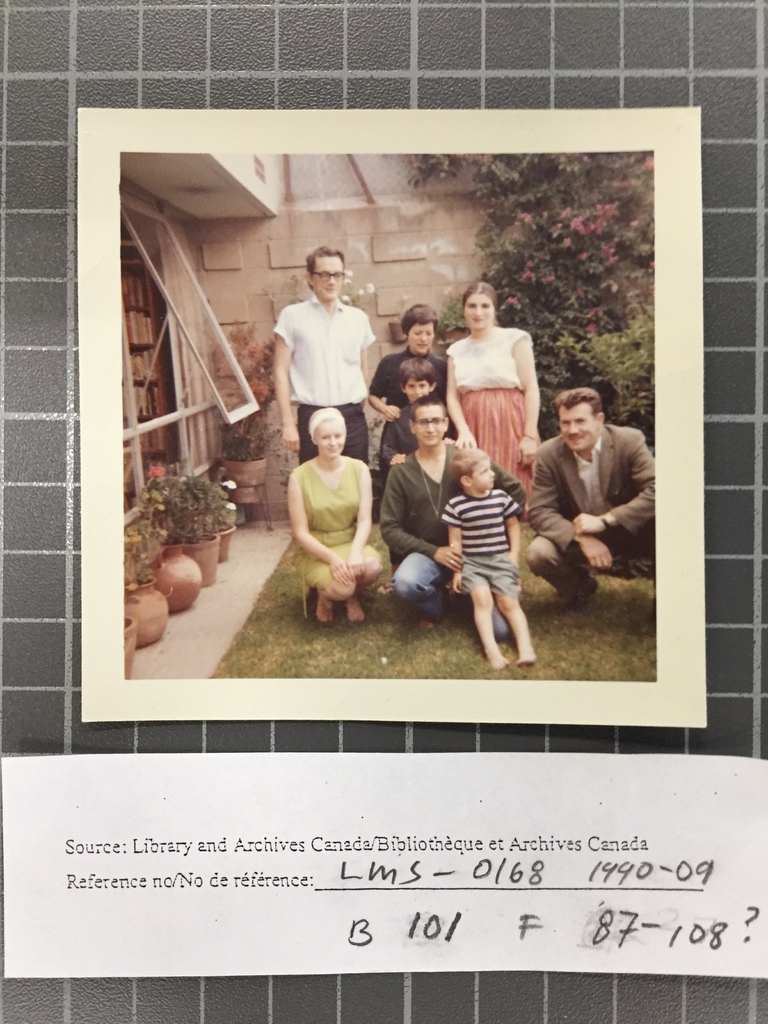

In October 1965, Margaret Randall and Sergio Mondragón published the Canadian poet George Bowering’s third book of poetry, The Man in Yellow Boots / El hombre de las botas amarillas, as the sixteenth issue of El corno emplumado.[1] This publication represented the culmination of two years of correspondence including month-long visits to Mexico City by Bowering and his wife Angela in the summers of 1964 and 1965. I am interested in the relationship between Bowering and Randall for the alternative configuration of the sixties poetic avant-garde that it allows me to sketch. Re-writing accounts of avant-garde poetry in Mexico and Canada through the peripheral affiliation between Mexico City and Vancouver dislocates established accounts of transnational influence and exchange in either country, and accepted circuits of the literary avant-garde more broadly. In order to make visible this overlooked affiliation, my account relies on marginal materials, in particular the correspondence carried out by George Bowering and Margaret Randall during the 1960s. This correspondence is exceptional in both of their archives, occupying more space than almost any other either author carried out with any other interlocutor in the era. Though this volume is at least partially explained by the fact of two capacious letter writers each finding their match in the other, it should surprise scholars of either poet that they were among each other’s most frequent interlocutors during these years. Such correspondence was crucial to El corno’s mission during its run, as scholars like Alan Davison and Gabriela Aceves Sepúlveda have argued, while Eva-Marie Kröller foregrounds Bowering’s participation in epistolary circuits in her 1992 monograph on his work.[2] As the Bowering-Randall correspondence transited back and forth between Mexico City and Canada, the airmail letters that overleaped the United States provide an image for the type of affiliative contact I hope to trace—one capable of undoing standard spatialities of affiliative contact, confined by neither urban geography nor national borders, and importantly eluding the United States as a site of transnational connection or cachet. As Bowering and Randall planned The Man in Yellow Boots, Bowering enthused about the project, saying “What a good thing this will be for me, allow me to move myself away from trap of being a Canadian Poet!!!! This means a lot, and you cant [sic] imagine what.”[3]

In emphasizing the importance of El corno’s correspondence, Gabriela Aceves Sepúlveda connects Randall and Mondragón’s correspondence to their shared domestic space. Aceves Sepúlveda argues that

The intimate tone of some of the letters provides insight into the interpersonal relationships forged through the pages of the magazine and that manifested in physical encounters in Randall and Mondragón’s home. These meetings provided a space where relationships forged through mail correspondence were strengthened and projects cemented.[4]

Aceves Sepúlveda stakes out an equivalence between the magazine’s correspondence and Randall and Mondragón’s home, which they cultivated as a meeting place for artists and writers during much of the magazine’s run, embedding visitors in the rhythms and ruptures of a home filled with three small children and a literary magazine. Aceves Sepúlveda also calls specific attention to Bowering’s relationship with Randall and Mondragón in making this claim, as she writes that Bowering “fondly recall[ed] his visits to [their] residence in Mexico City.”[5] Aceves Sepúlveda even goes so far as to claim that “Bowering’s work became known and published in several Latin American magazines as a result of these meetings.”[6] She reinforces how crucial this quotidian space was to the magazine’s ability to function as a means of hemispheric contact, as she appears to claim that it’s only through Bowering’s contact with the Randall-Mondragón residence—rather than publication in the magazine—that he becomes known elsewhere in Latin America.

The literary exchange between Bowering and El corno brings into greater visibility the ways in which such transnational contact relied on the quotidian spatiality of the Randall-Mondragón home, rather than standard institutional frames. That is, in the provisional version of the argument staged here, I aim to nuance accounts of both the everyday that place too great an emphasis on the nation, and accounts of the transnational that rely too heavily on the institutional. I want to qualify my claim by noting I am not arguing here that either of these aspects of El corno or Bowering’s work make either particularly unique. Many magazines from this period similarly cultivated a transnational community through postal correspondence and the publication of this correspondence in their back pages—both Floating Bear and TISH, the Vancouver, Canada-based magazine that Bowering helped edit during the early 1960s, billed themselves as poetry “newsletters,” for example. Nor do I mean to argue that avant-garde scenes aren’t often organized around domestic spaces—James Schuyler’s Manhattan apartment provides another example of that phenomenon. Rather, I hope to use the way in which these two modes overlap in El corno emplumado—and particularly with Bowering’s The Man in Yellow Boots and the correspondence that surrounds it—as a means of rethinking the ways in which domestic spaces helped to fix transnational literary affiliations in this period more generally, and how this imbrication of the everyday in the transnational can help to revise accounts of the quotidian that are too strongly defined by national culture or accounts of transnational literary contact that privilege the histories of institutions.

***

Randall makes frequent references to the ways in which work on the translations for Bowering’s book was typically woven into the fabric of her and Mondragón’s daily life in her letters. At one point in the correspondence, Randall sketches a picture of the family’s afternoon:

now it is after lunch. sarita has just had her mangy hair cut by sergio, me and elena by turns, one holding her down while the other cuts. very fetching. goyo is drawing pictures of a gas station and the gas is going into the roof of a conveniently located car. sergio is sprawled on the bed giving it to the translation.[7]

Randall describes her and Mondragón’s translational practice embedded in domestic space, no different from the other activities that take place within it. Yet this embedding of translation in quotidian space extends beyond the domestic sphere. Elsewhere in the correspondence Randall relates that “we have just finished translating eight of your poems … in first draft, that is. then sergio spends a week or so in the parks, with that first draft, putting in the music.”[8] Randall elaborates on this claim in the next letter by noting that “sergio took four poems into town yesterday and in parks and whatnot (also in office waiting rooms!) put them in perfect form!”[9] Bowering responds to Randall with the comment: “So strange to sit here, Calgary and imagine you in bedrooms and parks fixing up my poems.”[10] The translations circulate between and join the multiple sites and temporalities of what is typically registered as the everyday in twentieth-century cultural theory—transiting between the feminine domestic sphere of the home and masculine public space. The wide range of Randall and Mondragón’s quotidian orbit so fascinated Bowering—as it does me—that he elsewhere asserts that he’s “got the idea of making a film about Sergio and his household – all the things he does in a day in Mexico City.”[11] Yet the texts that Randall and Mondragón produced differ from the sort of everyday-life-focused poetry that Andrew Epstein discusses in his recent volume Attention Equals Life (2016)—where he takes up work by writers like James Schuyler and Bernadette Mayer that track the unfolding of consciousness within the everyday.[12] Yet Epstein pointedly locates this work within the frame of a U.S. national culture and public. Looking instead at Randall and Mondragón’s translations, these poems are rooted in the transnational even as they emerge from the quotidian spaces of Randall’s and Mondragón’s everyday life. Though I remain interested in the ways in which Mondragón’s movements through the public sphere suggest a strange sort of poetics of place expressible through the sonic materiality of works in translation, I’m going to focus for the remainder of this brief essay on the space of their home.

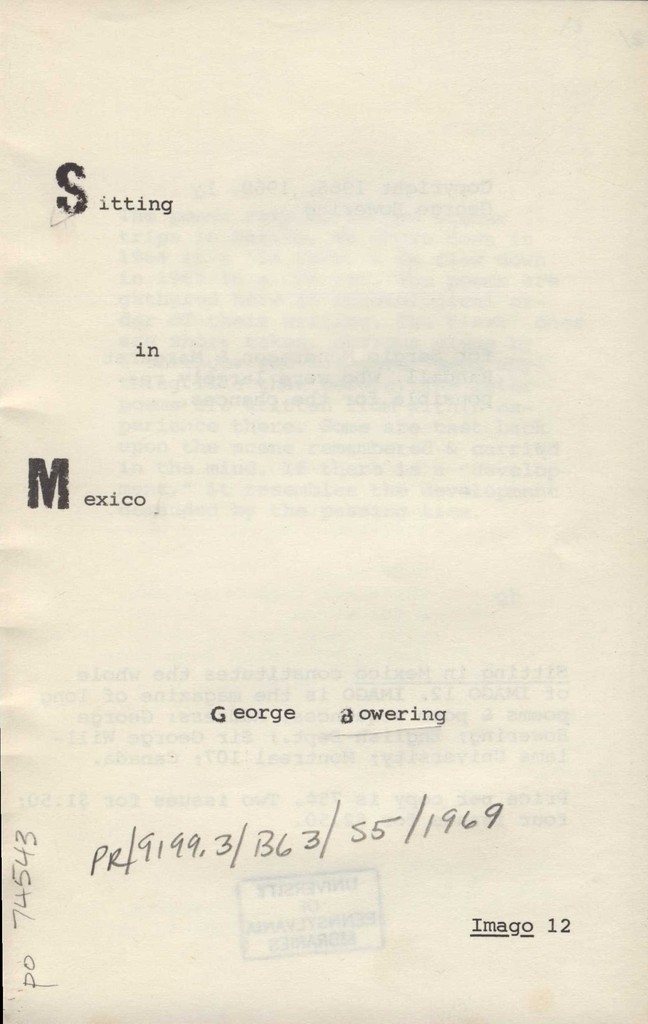

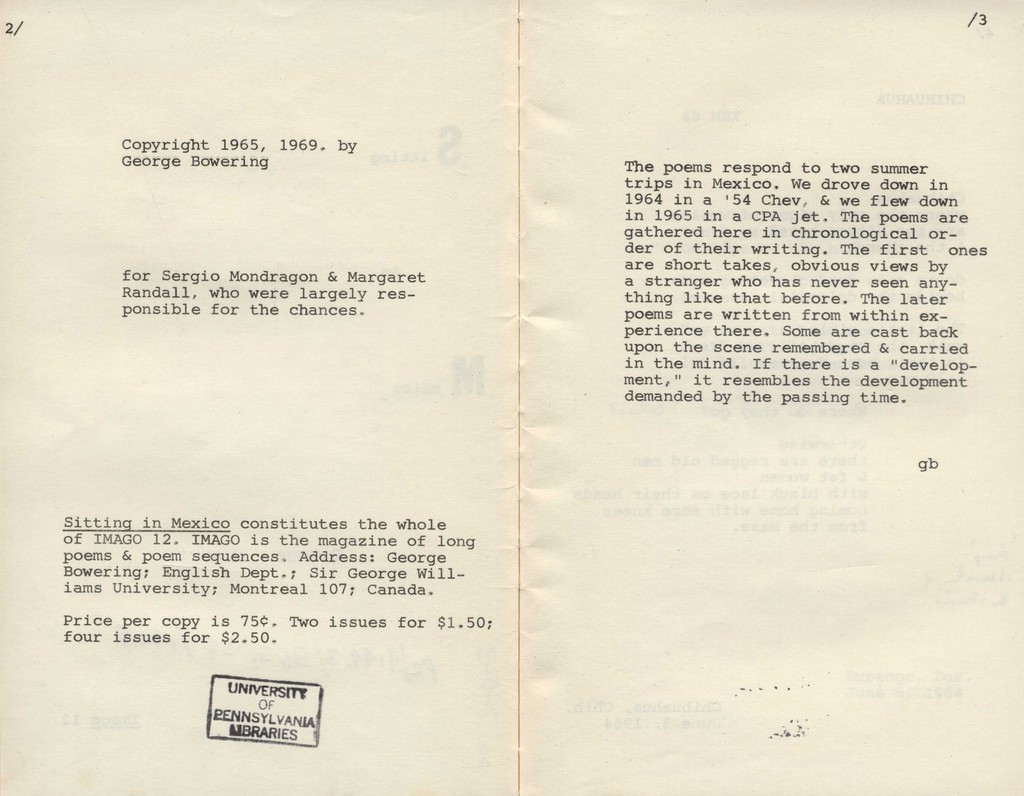

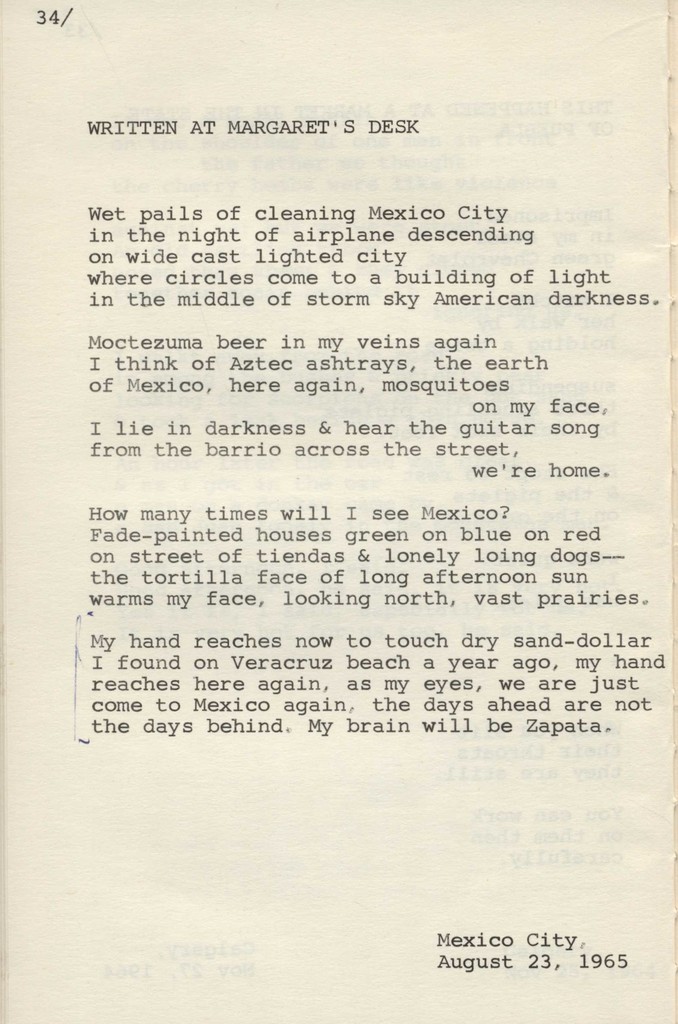

I want to pivot here to focus on an actual poem, albeit one that doesn’t appear in any issue of El corno, though it is intimately connected with the context I’ve just laid out. From 1964 to 1974, Bowering edited a poetry magazine called Imago,dedicated to publishing longer works of poetry and, like El corno, typically dedicating one issue per year to work by a single author. (Randall was, of course, a frequent contributor to Imago.) In 1969, Bowering published a collection of his own poems that chronicle his contact with Mexico, under the title Sitting in Mexico, as the twelfth issue of the magazine. As the dedication to this volume makes clear, the poems were made possible through Randall’s and Mondragón’s generous and generative friendship, and many of the poems take place within their Mexico City orbit. In “Written at Margaret’s Desk,” composed during Bowering’s second visit to Mexico City in August and September 1965, Bowering sketches out a vision of hemispheric belonging centered on the Randall-Mondragón household. The poem embeds this sense of non-national belonging within the quotidian temporality of “habit” that Bowering develops based on repeated returns to this domestic site.[13] Bowering begins by establishing an atmosphere that acts as a means of transnational connection:

Wet pails of cleaning Mexico City

in the night of airplane descending

on wide cast lighted city

where circles come to a building of light

in the middle of storm sky American darkness.[14]

The stormy night sky that surrounds Mexico City connects the “building of light” at its center to the rest of the hemisphere both through the figure of the airplane and the intercontinental dimension of “American darkness.” The “airplane” signifies as transnational both by serving as the mode of transport that had brought Bowering and his wife to Mexico City on their second visit, but also, importantly, as the medium of Randall and Bowering’s airmail correspondence. Moreover, in Bowering’s usage, “American” typically signifies in the broader hemispheric sense, unusual among Canadian writers. Bowering typically uses “USAmerican” as the adjectival form for things pertaining to the United States, rather than the anglophone “American.” This usage has been treated by critics in Canada as a personal (though political) quirk of Bowering’s, rather than a fairly standard gesture easily recognizable to anyone working in a Latin American context. As a result, Bowering’s use of the word “American” here freights the darkened sky with a continental resonance, underlined by the presence of the descending airplane.

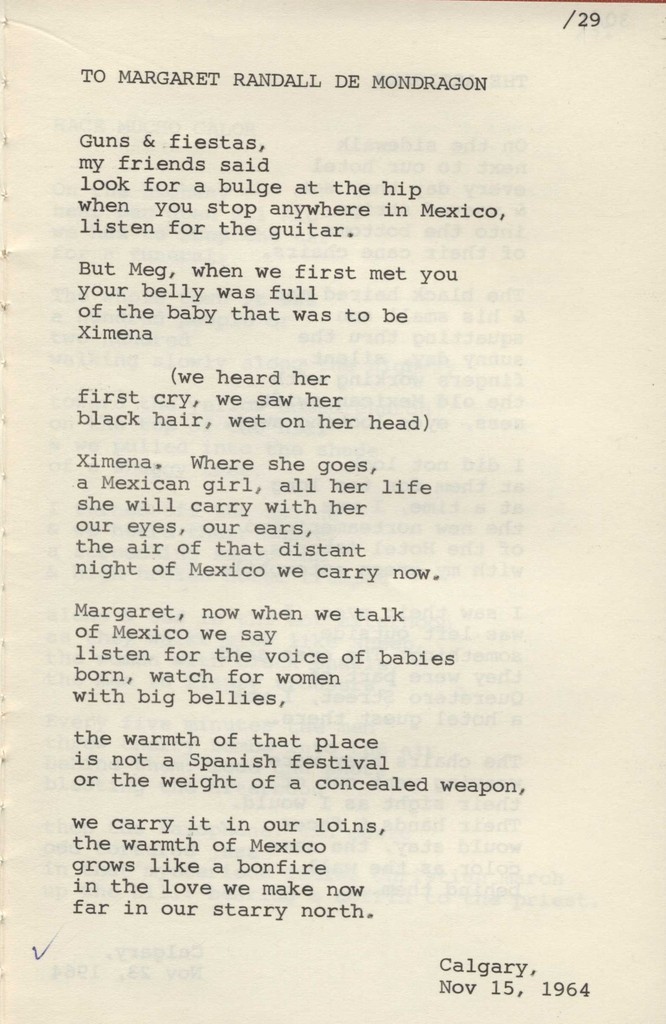

As the poem continues, Bowering locates himself more precisely as occupying a space within the Randall-Mondragón home and begins to cultivate a sense of the habitual in his approach to that domestic space and Mexico more generally. In the second stanza, Bowering calls attention to the “Aztec ashtray” which he mentions in an earlier poem, “Dolores Street Music,” written the previous summer. The appearance of the ashtray in these two poems composed a year apart helps to frame my point here. In each of the stanzas that follow from the opening invocation of the continentally-signifying rainstorm, Bowering emphasizes recurrence, from having “Moctezuma beer in [his] veins again,” to querying “How many times will I see Mexico?” to the final stanza in which he writes that “My hand reaches now to touch dry sand-dollar / I found on Veracruz beach a year ago, my hand / reaches here again, as my eyes, we are just / come to Mexico again.”[15] Through the quotidian objects of Randall’s study—the ashtray, the sand-dollar, the desk, the typewriter—Bowering builds a sense of routine that joins Canada and Mexico, a connection built on travel and habituation located in the domestic space of the Randall-Mondragón home. As he insists at the end of the second stanza, “I lie in darkness & hear the guitar song / from the barrio across the street, / we’re home.”[16] Bowering’s attention lingers on the ways in which the spatiality of the home cultivates this sense of both the quotidian and the transnational: how Bowering, as a Canadian subject surrounded by signifiers of Mexico, writing under a continental sky, builds a sense of quotidian transnationality. Much like Bowering and Randall’s correspondence, “Written at Margaret’s Desk” formulates a sense of the transnational or the hemispheric that relies on the quotidian, as much as he constructs a sense of the everyday freighted with transnational resonances. Though “Written at Margaret’s Desk” nonetheless mobilizes some of the standard tropes of tourist representations of Mexico—and if there is a single word that might stand in for the phrase “the quotidian transnational,” it’s almost certainly “tourism”—the other poem from Sitting in Mexico that directly references Randall, “To Margaret Randall de Mondragon,” invokes reproductive energies that George and Angela Bowering absorb from Mexico, suggesting another mode of transnational affiliation that might complicate simple tourist exoticizations, offering instead a bizarre genetic lineage of continental connection. As a parting thought, it’s worth recognizing that it’s not the movements of Mondragón through the masculine public sphere that cultivate this sense of transnational belonging in the materials I’ve laid out—in fact, Mondragón’s movements thru this sphere were often tied precisely to attempts to secure funding from nationalist state institutions—but rather this sense of hemispheric connection emerges from within the domestic, feminized space of the home.

[1] George Bowering, The Man in Yellow Boots / El hombre de las botas amarillas, ed. Margaret Randall and Sergio Mondragón, trans. Sergio Mondragón. (Mexico City: Special Issue of El corno emplumado, no 16, (1965)).

[2] Alan Davison, El Corno Emplumado The Plumed Horn: A Voice of the Sixties (Toledo, OH: Textos toledanos, 1994); Gabriela Aceves-Sepúlveda, “Artists’ Networks in the 1960s: the Case of El Corno Emplumado/The Plumed Horn (Mexico City, 1962-1969),” in The Global 1960s: Convention, Contest and Counterculture, ed. Tamara Chaplin and Jadwiga E. Pieper Mooney (New York: Routledge, 2017): pgs; Eva-Marie Kröller, George Bowering: Bright Circles of Colour (Toronto: Talonbooks, 1992).

[3] George Bowering to Margaret Randall, 26 January 1965, The El Corno Emplumado Papers, the Ransom Center, University of Texas, Austin.

[4] Aceves-Sepúlveda, “Artists’ Networks in the 1960s,” 203.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Margaret Randall to George Bowering, 3 December 1964, The El Corno Emplumado Papers, the Ransom Center, University of Texas, Austin.

[8] Margaret Randall to George Bowering, 2 August 1965, The El Corno Emplumado Papers, the Ransom Center, University of Texas, Austin.

[9] Margaret Randall to George Bowering, 4 August 1965, The El Corno EmplumadoPapers, Ransom Center, University of Texas Austin.

[10] George Bowering to Margaret Randall, 11 August 1965, The El Corno Emplumado Papers, the Ransom Center, University of Texas, Austin.

[11] George Bowering to Margaret Randall, 8 November 1964, The El Corno Emplumado Papers, the Ransom Center, University of Texas, Austin.

[12] Andrew Epstein, Attention Equals Life: The Pursuit of the Everyday in Contemporary Poetry and Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[13] Here I borrow from Rita Felski’s tripartite definition of “the everyday” as founded on the spatiality of the “home,” the temporality of “routine,” and the attitude of “habit.” Rita Felski, “The Invention of Everyday Life,” New Formations, 39 (1999): 15-31.

[14] George Bowering, Sitting in Mexico (Imago, 12 (1969)): 34.

[15] Ibid. Emphasis added.

[16] Ibid. Emphasis added.